Part 1: The Nazi Strategy of Concentrating People

Adolf Hitler and Nazi SS Chief Heinrich Himmler review the SS at a Reichsparteitag ceremony (Reich Party Day) in Nuremberg, Germany, September 1935. Photo credit: USHMM #11775

The origins of Nazi concentration camps began with Adolf Hitler’s political rise and eventual consolidation of power in 1933. Hitler, who first was appointed as chancellor before declaring himself the supreme leader of Germany (“Führer”), was obsessed with racial purity—partially inspired by the United States’ racist history and its eugenics movement—and believed that it was Germany’s destiny to rule the world. At first, few people took him seriously, but things drastically changed during a global depression in the 1930s that left millions of Germans unemployed after their defeat in the World War I. Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (also known as the Nazis), gained popularity by promising a better life and restoring Germany’s greatness with a new empire, the “Third Reich.”

Members of the SA drive through the streets of Recklinghausen, Germany with anti-Jewish banners during a propaganda parade. One banner reads, “He who knows the Jew knows the Devil.” The banner in front depicts a German man using a swastika to crush Jews who are shown with snakes coming out of their heads. August 18, 1935. Photo credit: USHMM #80821

Hitler blamed Germany’s problems on Jews and other so-called “racial enemies.” The Nazis were racists, believing that each person’s traits and characteristics were biologically determined. They believed that the white Germanic race (Aryans) was innately superior to other races, and had been weakened by disloyal and foreign elements. Jews in particular were seen as a “parasitic race,” who grifted off other people and did not belong in Germany. Once Hitler took power, these hateful ideas were taught in German classrooms and spread through newspapers and other media outlets, including flyers, radio programs, and propaganda films. This public campaign of discrimination and harassment effectively marked the beginning of the Holocaust—the state-sponsored persecution of the Jewish people (also known as “the Shoah”).

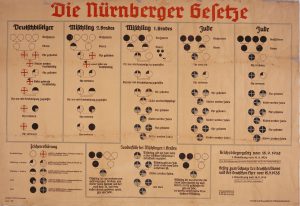

Jews suffered daily persecution after Hitler gained power, enduring economic boycotts and the repercussions of the 1935 Nuremberg Race Laws. These discriminatory laws defined a Jew as someone with three or four Jewish grandparents (blood relations) rather than by their religious beliefs. Additionally, the Nuremberg Race Laws revoked the citizenship of German Jews, depriving them of their political rights, and criminalizing sexual relations between Jews and Aryans. These restrictions were also extended to other non-Aryan groups, such as Roma and Sinti, Black people, and the developmentally disabled. The Nazis also began viewing Slavic peoples (Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, and Belorussians, to name a few) as racially inferior, frequently labeling them as “subhuman.”

Nazi infographic detailing “Die Nurnberger Gesetze” (Nuremberg Race Laws). The chart delineates “Deutschbluetiger” (German-bloods); “Mischling 1 Grades” (Half-breed Grade 1); “Mischling 2 Grades” (Half-breed Grade 2); and “Jude” (Jew). September 15, 1935. Photo credit: USHMM #N13862

Nazi ideology claimed that races were engaged in a struggle for global domination. To wage this “total war,” as the Nazis conceived it, they decided to group their enemies in close quarters—literally “concentrate” them—by building an extensive network of camps and ghettos. They did this for three reasons:

1. to purify the German race and promote Aryanism;

2. to conquer and colonize lands outside of German borders; and,

3. to use non-Aryans for forced labor.

Between 1933 and 1945, Hitler’s regime and its European allies imprisoned approximately 22 million people in a system of 44,000 camps and ghettos across the European continent. None of these sites were exactly the same, and each prisoner’s experience could be radically different, but all were a result of the Nazi’s drive to dominate Europe and turn it into a supreme Aryan state—one devoid of Jews.

Although similar camps were previously organized in the nineteenth century by Great Britain, Spain, and even the United States, the camps and ghettos devised by the Third Reich were distinct in terms of their scale and deliberate purpose of forced labor, brutalization, and extermination.